? | Home page | Tutorial | Recording

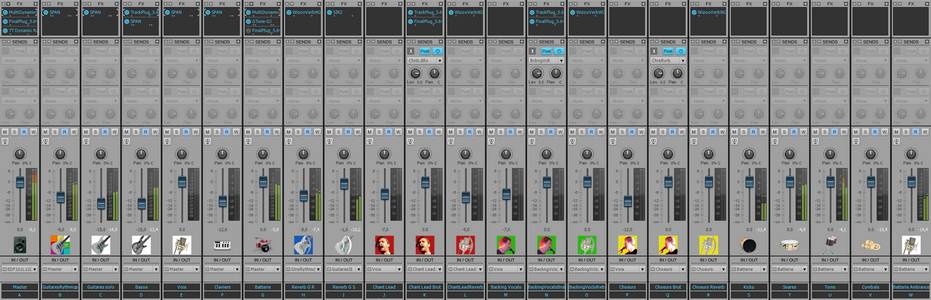

Before anything else, we need to prepare the recording session. We are not going to look for a melody, nor improvise or rehearse... we are going to properly record a song that we have already written. To avoid doing the same things over again each time I wish to record a song, I prepared a blank template which contains all the tracks and buses I need. I may naturally add or delete some elements if the template is not appropriate for the current project.

What does my template look like?

Track-wise:

- Rhythm guitar tracks (from 2 to 8 depending on the project)

- Solo guitar tracks (usually 2 tracks to make the sound thicker)

- Two bass tracks (one with the direct raw sound, and one with an amp simulation)

- Lead vocal tracks (usually one or two tracks, depends if I record it twice or not)

- Background vocals tracks (if the project demands it)

- Keyboard tracks (same thing, the number of virtual instruments will depend on the project, can be none, can be 5 or 6...)

Then we have drum tracks. There is one track per drum element. They are automatically created when I insert my virtual drum plugin:

- Kick drum

- Snare drum

- Low tom

- Medium tom

- High tom

- Hi-hat

- Crash cymbal

- Ride cymbal

- Splash cymbal

- Overhead microphone

- Room Ambiance microphone

- Piezzo microphone

- One MIDI track on which the drum score will be placed.

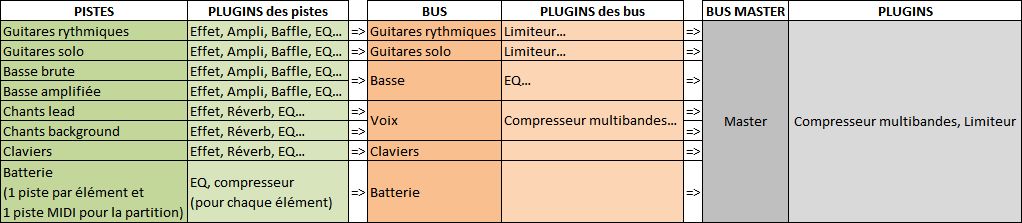

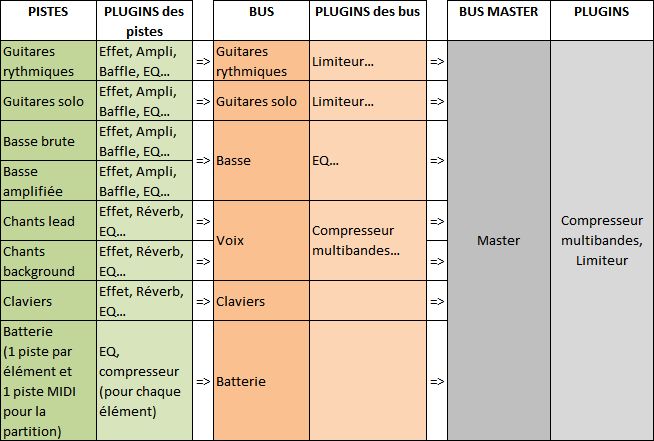

Bus-wise, I have one group for the guitars, one for the bass, one for the vocals, one for the drums, each of them is redirected towards the Master bus, which goes out throuh my studio monitors. It looks like this:

Recording an acoustic real drum kit is far from being easy, even for professional sound engineers. It a time-consuming process, it's frequent to spend several hours placing the microphones around the drum elements before you can actually record. But we are in a home studio, and we will have to deal with a software drum kit, based on midi files...

First of all, why start with the drums? The answer is simple, we will use drums as a metronome. The drums sound will guide us and help us follow the tempo. This will allow for an even recording and the song will not speed up or slow down unintentionally. Of course, variations can be interesting and bring some life to an otherwise mechanical tempo, but let's consider that a studio session seeks recording perfection, even though it's only a home studio.

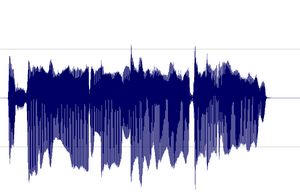

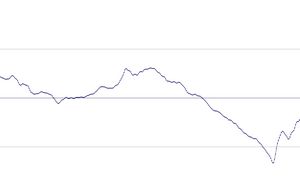

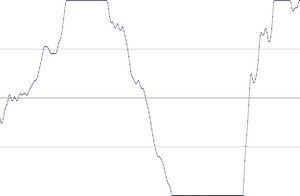

I usually have no idea what my final drum track will sound like. Actually, I only adjust it when the rest of the song is finished. But I still need its metronome function to record all other instruments. Thus, I create a drum track which repeats itself over and over again, and I try to have this loop match what I am about to play (no punk rhythm to record a ballad). For instance, I'll use one of these patterns:

Let's not forget we are recording in a home studio, in an appartment and it is simply impossible to play with a good old 100-watt tube amplifier, without the neigbors calling the police. So we are going to have to record the guitars and the bass directly through the audio interface. No real amplifier, no microphones involved. The latter solution would be preferable, but on of the benefits of direct recording, coupled with amplifier simulators, is that you can always edit the sound later, without having to re-record. Just change the settings and you're done.

So now... bass or guitars first? There isn't one clear answer. Bass and drums are the foundation, the rhythm base of a song and everything else should rely on them. But other factors could also be taken into consideration: for instance, the person recording may be more comfortable with a guitar than a bass, and will rather play guitar first. Or maybe the song has a very important bass riff that compels you to record it first. In any case, you are the one who can decide. If you are uncertain, then the drum / bass duo is a safe bet. If this is in place, then the rest can easily be added.

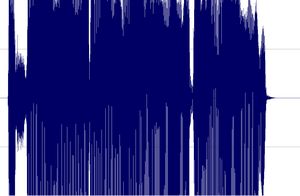

Guitar or bass, the recording process will be the same. Plug your guitar into the pre-amp, the pre-amp is connected to the audio interface (or plug your guitar directly into the audio interface if using the interface's pre-amp), and set the recording level. This is very important! Before recording anything, check that you are not going to go beyond the maximum level (0 dB, zero decibel). In a home studio, you won't have a sound engineer besides you to make adjustments on the fly, while you are playing. You are the one to take precautions. How can you do that? Simple: try and adjust, it doesn't take long and will prevent you from making a perfect take, then realize the levels were too low or too high, forcing you to do it all over again.

Have a try: for a rhythm guitar for example, play the loudest parts and set the preamp and audio interface volume levels in such way that when you play the loudest, the recording level doesn't go beyond -6 dB. The absolute maximum that you should not reach or go beyond is zero dB. If you play in your try the same way you play during the actual recording, then you can be certain the recording level will be correct. If your average level is between -9 db and -6 dB, then your level is sufficient and you have a margin of error before clipping.

Clipping is the term used to indicate that you reach or go beyond 0 dB. Clipping is your enemy :-)

I prefer to record them last but there are no rules. If you prefer to record them first, then do so.

To record vocals, make sure the place is quiet, shut the door, tell the people who live with you to be quiet, and do not record while your neighbor is drilling holes through his kitchen walls! Also, turn off your monitors and use a headset instead to avoid recording the playback with your microphone.

Condenser or dynamic microphones?

Dynamic microphones are solid, they don' need a power source, they can take heavy acoustic pressure (like a kick drum or a saxophone) and they are not too expensive. They are also less sensitive to surrounding noises than condenser microphones. The cons are they lack clarity in the high range, which renders takes less clear and defined than with condenser microphones. They can be used with Jack or XLR plugs.

Condenser microphones are much more responsive and accurate. Their high sensitivity is double-edged, because they will capture any noise when recording. The fans of your PC are noisy? Chances are this noise will be recorded. Sound comes out of your headset? It will be recorded by your condenser microphone. Children are loudly playing outside? You might get that too. However, some condenser microphones are called "cardioid", or "hyper cardioid", and they only record what comes from a specific direction, ignoring (more or less) other sound sources from other directions. On the contrary, omnidirectional microphones record what comes from anywhere. Not ideal for a home studio. Condenser microphones are also more fragile (don't knock them) and must be powered through a "phantom power", whose standard is 48 volts. This kind of power is either present on your audio interface and can be turned on and off with a button, or it will require the use of an external phantom power source that you will then connect to your audio interface. You have to use 3-pin XLR plugs that carry the phantom power current. Finally, condenser microphones are usually rather expensive, some of them cost several thousand euros (or dollars, or pounds), but only professional studios or rich amateurs can afford those. On the plus side, the sound you get with a condenser microphone will have the best quality.

Be cautious though, a good dynamic microphone is worth better than a bad condenser microphone. No big secret here, for microphones like for anything else, very low prices are rarely synonymous with good quality.

A few known and renowned microphone brands: AKG, Milab, Neumann, Rode, Sennheiser, Shure...

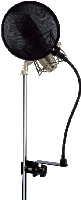

Some pieces of advice: buy a microphone stand and a pop filter (you can also make one yourself with wire and a piece of tights from your wife / girlfriend / mother / daughter / neighbor). The stand will prevent you from manually holding your microphone and thus produce handling noises. As for the pop filter, it prevents the air to hit the microphone and produce unwanted blowing sounds when you pronounce some letters such as "p" or "b".

Jack plug (left) and XLR (right)

No need to go on and on forever, recording is rather easy. As long as you pay attention to your recording levels and take care over your takes, you should get a satisfying result, good enough to finalize the song

Messages page # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35

Beber

le 21/12/2010 à 14h57

Salut,

J'ai vu que tu possèdes une I/O2. Je voudrais pouvoir utiliser la mienne sans PC en la branchant sur secteur via un transfo USB (objectif : jouer au casque avec mon RP 500 DIGITECH).

Mon multi-effet possède déjà une sortie casque mais le signal est trop faible, j'ai donc besoin de sortir sur l'I/O2 avec mes XLR puis d'utiliser la prise casque de l'I/O2.

PS : joli site et beau matos !!!

bibize

le 15/12/2010 à 15h59

Bonjour,

Concernant le mixage, je ne comprends pas l'intéret de créer un bus "Brut" qui joue la guitare sans effets.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

<em><strong>Pour une guitare électrique, ça n'a effectivement pas vraiment d'intérêt</strong> et je n'utilise plus ce bus. Je l'ai récemment supprimé de mon modèle de projet.

En revanche, <strong>pour une guitare acoustique, c'est beaucoup plus intéressant</strong> bien entendu.

Grebz</em>

Jukap

le 28/11/2010 à 00h00

Pour la fréquence d'échantillonnage, c'est relativement inaudible entre 44 et 88 pour un enregistrement (sauf peut-être conditions de chaîne audio parfaite), par contre cela devient TRÈS intéressant dès qu'il existe un TRAITEMENT DU SON DANS LE DAW : EQ, comp, simus, réverbes, etc... On gagne très rapidement en définition et profondeur lorsqu'on augmente la fréquence d'échantillonnage et là pour le coup, le 96 prend son sens (par contre, ça met vite à genoux le processeur...).

Jack

le 27/11/2010 à 23h32

C'est quoi que tu appelles Bus ?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

<em>Un bus se présente visuellement comme une piste, mais au contraire d'une piste, le bus ne contient aucune donnée (pas d'audio, ni de données MIDI). En revanche, tu peux y appliquer des effets et agir sur de nombreux paramètres (volume, panoramique, données d'automation...). Ils servent souvent à regrouper les données venant d'autres bus ou de plusieurs pistes en un seul endroit afin de pouvoir contrôler d'un bloc plusieurs pistes par exemple (passer en Muet toutes guitares d'un coup, ou ne mettre en Solo que les synthés, etc.)

Exemple d'utilisation d'un bus : tu crées 3 pistes de guitares, et tu souhaites leur appliquer un traitement commun, comme par exemple la même réverb.

Au lieu de mettre 3 fois la même réverb sur les 3 pistes de guitares, tu crées un bus, tu indiques à tes 3 pistes de pointer vers ce bus et tu appliques l'effet réverb sur le bus.

Résultat : tes 3 guitares auront la même réverb, mais tu n'auras utilisé qu'un seul plugin. Avantages : moins d'utilisation processeur avec une seule réverb qu'avec trois, et si tu souhaites modifier la réverb, tu n'as pas besoin de le faire 3 fois.

Autre exemple : tu souhaites appliquer des effets différents à une guitare présente sur une piste. Au lieu de créer plusieurs pistes, tu crées plusieurs bus, tu fais pointer ta piste vers chacun de ces bus, et sur chacun d'entre eux, tu places des effets différents (des simulateurs d'ampli différents, des panoramiques différents, des pédales d'effets différentes, des EQ différents, des volumes différents, etc...)

Au final, en n'ayant enregistré qu'une seule piste de guitare, tu pourras donner une grande richesse sonore à cette unique piste, tu pourras donner l'impression qu'il y a plusieurs guitares...

Grebz

</em>

Tekk

le 22/11/2010 à 09h51

Super boulot ! . . . Félicitations